Indirection Is Not Abstraction

The concept of abstraction in software development is frequently misunderstood and confused with indirection. This is partially because of the keywords abstract and interface in statically-typed languages such as Java and C#. The confusion often leads to design changes that leave the code worse than before it was touched. Let’s look at how abstraction and indirection relate, and how to correctly connect components.

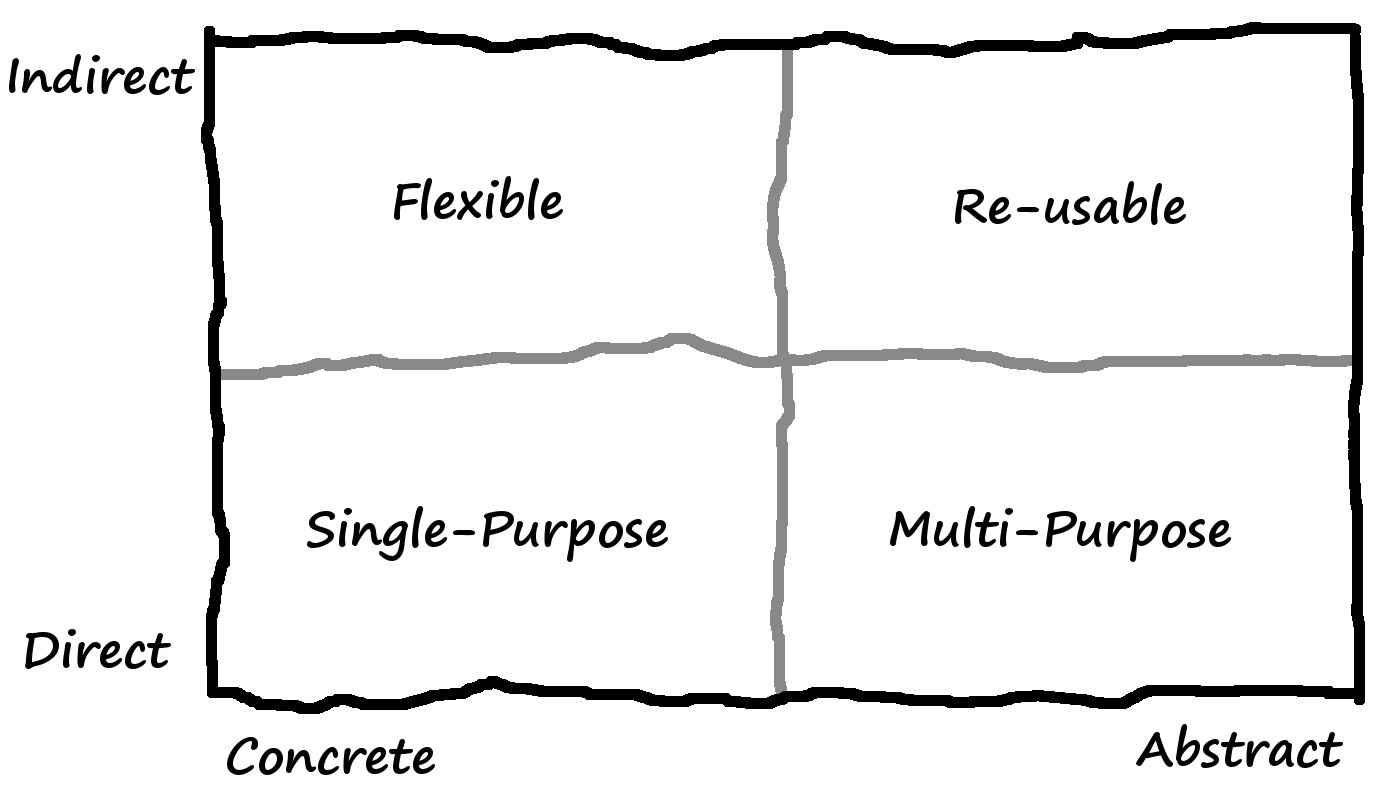

The Two Dimensions of Software Variability

There are two different dimensions in play here. Both of them are important for creating simple, flexible, usable software. The first dimension is the degree of coupling. High coupling occurs when things are directly connected. Low coupling exists where things are indirectly connected. Neither high-coupling nor low-coupling is inherently good or bad. It’s contextual. Things that are directly connected are simple, faster to build, and easier to understand. However, they are inflexible. When there are expected dimensions of software change, it can be worth paying the cost to create software with higher flexibility. Flexible software is harder to create, more complex, harder to understand, and harder to maintain.

The second dimension is about level of abstraction. Low abstraction (concrete) occurs when details are very specific and explicit. High abstraction occurs when all details are left out, and only general concepts are communicated. Low abstraction in software operates with full knowledge of details such as memory addresses, pointers, threads, registers, encodings, http status codes, etc. High abstraction in software operates in business concepts such as calendars, schedules, orders, customers, slides, pictures, etc. Things which are more abstract are more generally usable, and are easier to reason about. Things which are more concrete are what enables and empowers the abstractions – they make everything work. Without concrete elements, software is nothing more than a beautiful shell of uselessness.

- Direct: I will hand Bob $70 cash for his old lawnmower.

- Indirect: Bob has agreed that his company will deliver a lawnmower to my house after processing my credit card payment online.

- Concrete: I ordered a lawnmower from www.bobsgardeningsupplies.com earlier today using my old Visa card ending in 9872.

- Abstract: I bought a lawnmower.

Directness is about how many elements are in between two parties.

Abstraction is about how many details are expressed and involved.

Software Examples

Languages such as C# and Java have done many a disservice with their keywords abstract and interface. There is a common misconception that by creating an interface one can make an object abstract and improve the design of a system. Introducing a new interface only introduces an indirection. It does not change the abstraction level. Consider the following:

public int AddThree(int val)

{

return val + 3;

}

public int AddThree(int val)

{

return val + new Three().AsInt();

}

private readonly IThreeProvider _threeProvider;

public int AddThree(int val)

{

return val + _threeProvider.Get().AsInt();

}

Nothing about the behavior of the algorithm has changed.

- In the first example, the number 3 is use as a constant primitive value at the call site.

- In the second example, the value 3 is encapsulated inside a concrete object, and may or not be represented internally as an integer.

- In the third example, there is some implementation who will provide us with 3, but we do not know where that number is sourced from.

The level of directness changed. First we coupled directly to the integer value. Then we used an intermediary class to avoid directly sourcing the integer value. Then we hid the specific class implementation from the function. However, the algorithm is not more abstract. We can never use a 3, or a Three or an IThreeProvider for anything except in algorithms that require the specific whole number 3. This is not very re-usable. It can’t be used in a general purpose calculator. It doesn’t work with any number. The users of this software would be very disappointed if any of these indirections involved adding any number besides 3.

When a developer adds an interface to a class, but doesn’t change the possible usages of the class, nor reduces the number of required parameters, the abstraction level has not changed at all. The abstraction level of a class only changes if it requires a different number of parameters, or is usable across a different number of use cases.

Direct Yet Abstract

As an example of something that is used directly, implementations of String are very concrete. It exists as a single type in virtually every popular programming language. There is no indirection in usages of strings. Every piece of code directly depends on the native implementation of String. The implementation of string is relatively inflexible. However, strings are also incredibly abstract. They can be used to represent a very large range of things:

- A Person’s Name

- A Search Query

- Your Dog’s Age

- A Message

- A Transmitted Chunk of Data

- An Image

- … etc.

The usages are virtually limitless. If I tell you that I will be sending you a string, there are so few details that you won’t have any idea of what sort of information I will be sending you. You need further context if you want to put the string to use.

This is also why, sometimes you want types that are less abstract. It’s much easier to reason about and use a CustomerId or a DogAge than a string. There is more information available and more context, even if internally those value types hold a reference to a string. You can imagine what sorts of values might be valid or invalid for a DogAge or a TotalPrice or an EmailAddress.

This directness impacts portability, but not the range of possible usages. It is very easy to use a string for many possible software features. However, code that depends directly upon java.lang.String cannot be ported directly to Swift/Go/C#/etc.

The Dependency Inversion Principle

The Dependency Inversion Principle is about abstraction, not about indirection. Indirection doesn’t increase the usability (or re-usability) of software.

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

The key design implication is that the details should always be left out of the core design, so that the software isn’t dependent on them. If your software is about selling cars, then changing payment processors shouldn’t impact whether or not you can sells cars. Moving your data from Hadoop to SQL Server shouldn’t impact whether or not you can sells cars. New tax laws in certain regions shouldn’t impact whether or not you can sell cars. Those are low-level details. They must be in the system, but the system should not depend on them.

If your game is about moving through levels collecting fruits, then then general functionality of the game shouldn’t be directly dependent on whether you character runs or walks, whether he is collecting watermelons or pineapples, whether there are 98 levels or only 17. Those are details. They must be part of the game design, but the game must not become unplayable because of any of those details.

However, for details at the same level of abstraction, there is no inherent virtue in adding layers of indirection. Details are absolutely allowed to depend on other details at the same level of abstraction. There is no merit in adding in interfaces and separating them out into separate files, unless that specific flexibility is needed.

A SQL-Speaking object who has a number of different database queries, may absolutely include joins to other SQL tables and return more complex data structures, if warranted. However, that object shouldn’t have any logic around deserializing Json, handling unicode string formats, validating emails address, nor should it house any logic of higher-order operations such as placing orders, scheduling transfers, authorizing payments, etc. It should exist at one level of abstraction, and delegate out any lower-level operations.

A Game HUD View object may absolutely know how to format numbers for displaying them in a Game Score Counter, and may directly depend on the Game’s Current Score, the Player Name, and other specific elements that are to be visualized. However, the rules for how the score is calculated, and the process for how the player configures his character should not depend on the HUD View. There is absolutely no problem with having just concrete classes for CurrentScore, PlayerInfo, Game, and HudView. The system will still remain structurally correct at long as the details are independent of the general game flow.

If you see developers advocating against static classes, concretely-coupled objects, or specific functions on the basis of the Dependency Inversion Principle, be sure that the conplaint is about the mismatched abstraction levels of those components, and is not just a general complain about lacking indirection. Adding indirection to your system doesn’t change the abstraction level. There are many indirections which are not abstract at all!

Design Implications

Neither abstract/concrete nor direct/indirect inherently have best values. Some things should be abstract, and other things should be concrete. Some dependencies should be direct, and others should be indirect. Great design, then, requires clear heuristics.

Directness Heuristics

- Make your components relate to each indirectly, when they will change for different reasons.

- Make your components relate to each other directly when they are trivial, or when they won’t have a need to change.

- If you don’t know whether or not a component will change, your software will be best if you assume it will not change. (YAGNI).

Abstractness Heuristics

- Make your components concrete when you don’t have a need to solve general problems.

- Make your components abstract when you will need to solve a very similar class of problems with numerous permutations.

- If you don’t know whether or not you will need to solve a whole class of problems, your software will be best if you assume that you don’t need a general solution. (YAGNI).

Keep your software as simple as possible, until it needs to become more complex. Complex software is very costly and painful, both to develop and to use.